The Tower of London is a castle located in London alongside the River Thames which was first built by William the Conqueror from c. 1077 and significantly added to over the centuries. Often referred to in England as simply 'the Tower', it has served as a fortress, palace, prison, treasury, arsenal, and zoo.

A castle with the darkest of reputations, fallen kings, queens, and traitors were amongst those sent to the Tower, although surprisingly few inmates were executed within the castle's grounds. Today, it is a major tourist attraction with visitors eager to experience for themselves a place steeped in the history of England like no other, to admire the picturesque Beefeaters, and be dazzled by the fabulous Crown Jewels.

The White Tower

When William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy won the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and embarked on the Norman Conquest of England, the new king sought to make his realm secure by building motte and bailey castles at strategically important locations. London was an obvious choice for a new castle and so work began on what would become the Tower of London around 1077. The castle was one of the first in England to have a free-standing tower keep or donjon. Work continued until c. 1100 using Kentish ragstone with details using dressed limestone from Caen in Normandy, and by the time it was finished, the two-storey rectangular tower was so impressive it gave its name to the whole castle: the Tower of London. The keep only received its now-famous name, the White Tower, thanks to a whitewashing project in 1240 using white lime.

The tower measures 36 x 32.5 metres (118 x 106 ft.) and is 27.5 metres (90 ft.) tall. Access was via a wooden staircase on the south side that reached to the first floor - this was protected by a short tower in the 12th century (destroyed in 1674). The first floor and the second were divided into unequally sized halls by a central cross-wall. It is not clear what these chambers were used for, and there is no record of William ever staying in the castle so perhaps it was originally intended as a showpiece of Norman power. A spiral staircase gave access to the upper floors, and a basement, likely used for storage, had access to a well. Chambers, toilets, fireplaces, chimneys, and drains were cut into the tower's thick walls. The tower had a sloping roof on either side of the cross-wall, and the top floor contained the chapel of Saint John the Baptist; its apse gives the tower its curved eastern corner. Inside, the chapel has an arcade of thick arch-bearing columns, a barrel vault ceiling and a gallery running around the sides. Three stained glass windows showing the Virgin and Christ child were added around 1240.

The castle was rather more than the tower, though, as it was surrounded by a curtain wall with corner towers. Two sides of this wall utilised old Roman walls which had been repaired by the Anglo-Saxons - probably the principal reason why William choose the site in the first place. The castle was given a protective ditch and a wood and earth palisade on two sides while the river protected the other two. In 1097 William Rufus converted the palisade curtain wall into stonework. The main entrance to the castle was on the west (city) side and protected by an elaborate barbican fortification. The structure, built at a 90-degree angle to the entrance for extra security, became known as the Lion Tower.

Multi-Purpose Home of the Monarch

English monarchs used the tower as an occasional residence up to and including Henry VIII (r. 1509-1547), and many of them made important additions and improvements over the centuries. In the 12th century, the massive polygonal Bell Tower (c. 1190-1200) was added to the southwest corner of the curtain wall, a tidal moat was dug (50 metres / 160 ft. wide), and the wall was extended on the south side so that more money was spent on the complex than any other English castle except Dover. Henry III of England (r. 1216-1272) paid particular attention to the apartments within the castle and even established a small zoo (although King John, r. 1199-1216, may have been the first to keep exotic pets here). Leopards, lions, an elephant and even a polar bear were all resident at one time or another, usually diplomatic gifts, and the Tower Menagerie only closed down in 1835. Another curiosity of the 12th century was the future Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket (r. 1162-1170) doing a stint as the castle's constable in the 1150s.

The Bloody Tower and the Wakefield Tower were added during the reign of Henry III of England (1216-1272), as were three D-shaped towers on the east side and three on the northern side of the curtain wall. In addition, the free-standing Great Hall was rebuilt (now gone), which measured 24 x 15 metres (80 x 50 ft.). Generally, though, the 13th century CE saw a trend towards increasing comfort rather than military security of castles. In 1240 an order stipulated for the

queen's chamber to be wainscoted…and to be painted with roses…a wall to be made in the manner of panelling between the said chamber and the wardrobe of the chamber [and] to be tiled outside.

(quoted in Pounds, 83).

Meanwhile, the king's chamber was painted with the royal arms and a turret added to the corner to act as a drain directly into the Thames after complaints from Henry III about the smell of the previous ensuite toilet. Another of Henry's projects was the almost complete rebuilding of the Chapel of Saint Peter ad Vincula in the northwest corner of the bailey.

The Tower was becoming multi-purpose, too. First, Edward I of England (r. 1272-1307), finally achieved the castle's permanent layout by completing the now double-circuit wall on the three land sides and adding the watergate structure known as Saint Thomas' Tower. The latter was used as the royal chambers and stood over the entrance that state prisoners were escorted through direct from the river: Traitor's Gate. Next, Edward moved one of the royal treasuries to the castle and made it the home of a royal archive (eventually settled in the Wakefield Tower) and the kingdom's main mint (in a row of little workshops with 30 furnaces known as Mint Street). Henceforth, the Tower also became England's main arsenal (where siege weapons, arms and armour of all kinds were made and stored). For greater security for all these valuable assets, Edward III of England (r. 1327-1377) ordered that all guards and officers remain within the castle at night with all gates being locked from sunset to sunrise.

During the reign of Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399), the basement was reinforced to bear the extra weight of the heavy guns stationed on the roof, some of which weighed 600 lbs (c. 270 kg). Also in this period, there was another 'before-they-were-famous' attachment with the Tower when Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343-1400) acted as the Clerk of Works before he established himself as one of medieval literature's most celebrated poets. From 1377 to 1661 the Tower even got a look-in on pomp and ceremony and hosted the start of a vigil procession on the eve of coronations. The soon-to-be new monarch traditionally spent the night in the castle before being crowned in Westminster Abbey. The royal robes worn in these ceremonies, along with many other precious textiles like tapestries, were all kept in the Tower Wardrobe. In the 1490s, a third floor was inserted into the tower, resizing those below, as indicated by still visible marks on the walls of the original roof eaves.

Famous Prisoners

One important function of the Tower was as a prison. A history of the inmates is like reading through a who's who of the history of England with many famous names ending up in the castle, some to be finally released and others to be executed - although only seven people were executed within the castle prior to the 20th century (most executions took place elsewhere such as Tyburn).

Oddly, there were no purpose-built cells prior to 1695, rather, prisoners were put in whatever chambers were available. People were most often imprisoned for political or religious reasons and so they tended to be important people fallen from grace. The accommodation might not have been so bad but confessions were frequently extracted by torture. This was the case with Guy Fawkes of the failed Gunpowder Plot to blow up Parliament, whose shaky confession-statement signature indicates his 10-day torment following his capture on 5 November 1605. Torture was rare but when it was used, the preferred methods were hanging the victims by their wrists, stretching them out on a rack or slowly crushing bones in the device known as the 'Scavenger's daughter.'

Henry VI of England (r. 1422-1461 and 1470-1471) was imprisoned in the tower for nine years during the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487) until he was saved by a Lancastrian army. This was to be only a temporary reprieve though, as a Yorkist army put Edward IV of England (r. 1461-1470 and 1471-1483) back on the throne and Henry found himself once more in his old prison, where, a month or so later, he was most likely murdered.

When Edward IV died in 1483, the Tower received two if its most infamous prisoners: the young sons of the dead king, Edward and Richard, known as the 'Princes in the Tower.' They were put their by Richard of Gloucester as he made himself king Richard III (r. 1483-1485) and within two months both princes were murdered with everyone, including Shakespeare in his play Richard III, pointing a finger of accusation at the usurper king. Two skeletons of youths were discovered near the White Tower when the forebuilding was demolished in 1674 and these remains, identified then as the two princes, were reinterred in Westminster Abbey. The remains were re-examined in 1933 and confirmed as young males of similar age to the princes.

Sir Thomas More (b. 1478), an opponent of the Protestant Reformation who refused to swear an oath recognising the king's supremacy as head of the church, was a prisoner of the Tower in 1534 until his trial and execution on 6 July 1535. He would later be made a saint by the Catholic church.

Anne Boleyn, Queen of England (r. 1533-1536) and second wife of Henry VIII of England, was kept in the Tower on charges of adultery and plotting to poison her husband, which she denied. Anne, whose real 'crime' was not giving Henry a male heir, was executed on the castle's lawn, the Tower Green, in May 1536, meeting her unjust death with great dignity. Catherine Howard (b. c. 1520), Henry's fifth wife, would meet exactly the same fate in 1542. Even Henry's daughter Elizabeth I (r. 1558-1603), while still only a princess, was sent to the Tower for a couple of months in 1554 by her suspicious sister Queen Mary I of England (r. 1553-1558).

The adventurer Sir Walter Raleigh found himself put in the Tower three times - once for marrying a lady without the queen's permission, then for plotting against James I (r. 1603-1625), and finally for violating a treaty with Spain while he was searching for El Dorado in South America. He at least was accompanied by his family in his confinement and found time to write poetry over the next 14 years until his execution in 1618.

The Tower did not always keep a hold of its prisoners; 37 got away, even if freedom was sometimes only temporary. One success was Roger de Mortimer (1287-1330) who had served as the king's lieutenant in Ireland but got on the wrong side of Edward II of England (r. 1307-1327). Imprisoned in the Tower, he had an ally drug the guards, allowing him to escape using a rope ladder and flee to France in August 1324. Roger would return and rule as regent of England but was eventually hanged by Edward III in 1330. Then there was the Jacobite Lord Nithsdale who gained his freedom in 1716 dressed in his wife's clothes and makeup. These examples show that prisoners were often confined within the vast castle grounds and not any particular part of it. However, escapes did not go without consequences, as when Ranulf Flambard (c. 1060-1128), the former Bishop of Durham, first wined and dined his captors and then escaped by climbing down a rope hung from a window; the constable of the castle was consequently stripped of one-third his lands by Henry I of England (r. 1100-1135) as punishment for his neglect.

Post-Medieval History

From the 16th century onwards the Tower was less of a royal residence - monarchs preferring Westminster - and became merely an armoury, barracks, storehouse (especially of gunpowder) and, as we have seen during the reigns of the ruthless Tudors, a (sometimes) terrible prison. The complex did continue to receive new buildings for various purposes, usually connected to the manufacture, testing, and storage of arms. These included the Grand Storehouse, completed in 1692. Indeed, the castle was becoming so packed with materials of war that the buildings were literally bursting. The flooring of the top floor of the White Tower collapsed under the weight of 2000 barrels of gunpowder in 1691; fortunately, no explosion ensued.

Despite its military redundancy as a fortress and the ravages of time, the castle would become one of the most glamorous weapons and treasure stores in history and, as time went on, it began to attract public visits for pleasure. In 1506 a garden was added. From the 1660s, the Crown Jewels were put on display in the Tower for the paying public to admire (see below). In the same century, the Armouries Building was added and the White Tower received its present turret roofs, new window surrounds and doorways. Fortunately, the Great Fire of London in September 1666 spared the castle. Great names continued to weave their way into the castle's history. Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727), for example, served as Warden of the Tower Mint in 1696 and was then the Mint Master for 28 years. In 1700 large windows in the White Tower replaced the smaller old ones as defence was no longer a necessary consideration.

In the 19th century, the Tower became a major military headquarters with a large garrison and the Waterloo Barracks added in 1845, which is today the headquarters of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers. Occasional fires took their toll on specific buildings such as the one that destroyed the Grand Storehouse in 1841 and several outer buildings were damaged by bombs during the Second World War (1939-1945). The castle, though, has continued to evolve with additions, demolitions, and restorations right up to the present day, largely in an effort to restore the castle to its medieval appearance.

The castle continued to be used as a prison into the early 19th century, with even unruly members of parliament not immune to incarceration. Even in the 20th century, important captives found themselves here. One of the last such inmates was Rudolf Hess, Adolf Hitler's deputy, who spent four days there in 1941.

Beefeaters, Ravens, & the Crown Jewels

The royal bodyguard, officially known as the Yeomen of the Guard (and by everyone else as the Beefeaters since at least 1700), were charged with guarding the Tower and its occupants from an unknown date sometime in the 15th century. The Yeoman Warders still patrol today - and act as tourist guides - wearing their striking red Tudor livery. As distinctive a presence on the grounds as the Beefeaters are the ravens. It is not known when these birds first arrived, but a legend goes that as long as they remain, the kingdom will endure. There was a very close call during the Second World War when bombing killed all but one of them. Fortunately, Gyp the sole survivor carried on the tradition, and they can still be seen today wandering across the lawns with that certain aloofness which comes with protected residency.

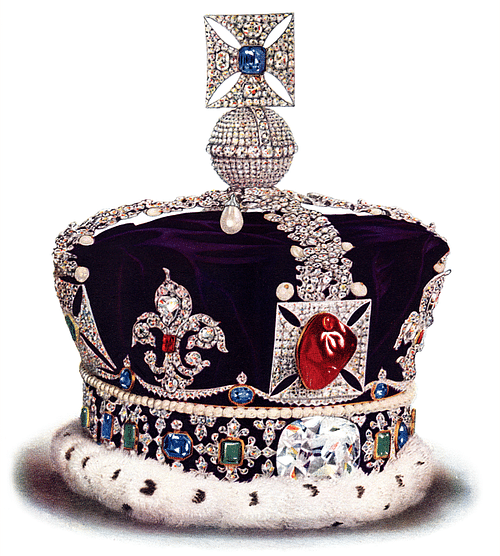

Today the Tower hosts displays from the Royal Armouries and, of course, the Crown Jewels. The imperial regalia, various items of which are still used in coronation and state ceremonies, includes crowns, rods, sceptres, swords, rings, orbs and a pair of spurs. Unfortunately, much of the original regalia was sold off and destroyed in 1649 following the execution of Charles I of England (r. 1600-1649) and the (what turned out to be) temporary abolishment of the monarchy. However, the replacements are impressive and many of them include recycled elements from regalia dating back to the 11th century.

Some of the largest and most famous gemstones in the world are found in the Crown Jewels such as the massive 530-carat Cullinan I diamond, also known as the Star of Africa, sparkling at the top of the King's Sceptre and the Black Prince's ruby (actually a balas or spinel), now in the centre of the Imperial State Crown worn by Elizabeth II at her coronation in 1953. This crown also boasts the Cullinan II diamond in it as well as the Stuart Sapphire, Saint Edward's Sapphire, over 2,800 diamonds, 15 more sapphires, 11 emeralds, four rubies, and even Elizabeth I's pearl earrings. The 105-carat Koh-i-Noor diamond from India has appeared in several crowns but now rests in the Crown of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother. Visitors today can admire these treasures in the Jewel House inside the Waterloo Barracks and stand on a moving walkway which, somewhat tantalisingly, transports them gently past the glittering glass display cases.