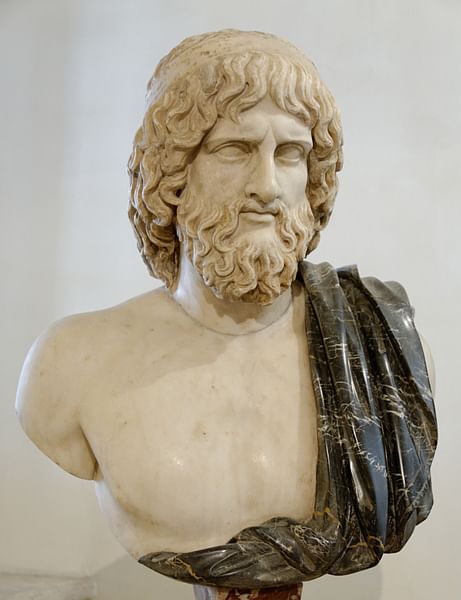

Pluto is the god of the Underworld in Roman mythology. His Greek counterpart was Hades. Pluto chose never to sit on Olympus with the other gods and goddesses, preferring to remain in the Underworld.

Family

Pluto (Hades) was the son of the Titans Saturn (Cronus) and Ops (Rhea) and the brother of Jupiter (Zeus) and Neptune (Poseidon). After conquering the Titans, Jupiter assumed the vacant throne of Saturn as the sky god and ruler of the world. Maintaining supremacy, he divided part of his realm between his two brothers: Neptune was granted authority over the seas and all rivers while Pluto gained control of Tartarus and the Lower World – sometimes called the Infernal Region or Hades – and as the ruler of the Underworld, he held dominion over the dead; it was the duty of the messenger god Mercury (Hermes) to conduct souls to the Underworld.

Pluto held court seated on an ebony throne next to his queen Proserpina (Persephone), but she was a reluctant queen. Kidnapped by Pluto and made a virtual prisoner, she was forced to spend three (some claim six) unhappy months a year in the Underworld; the remainder of the year was spent on earth as the goddess of vegetation. While Ceres (Demeter) was searching for her daughter after the kidnapping, she learned from the river nymph Arethusa, who had seen her daughter in the Underworld, that Proserpina "seemed sad indeed and her face still perturbed with fear, but yet she was a queen, the great queen of that world of darkness, the mighty consort of the tyrant of the Underworld" (Ovid, 98).

Character & Attributes

Unlike his brothers, Pluto not only invoked great fear in humans but he was also the most detested. He was "the grim robber who stole from people their nearest and dearest" (Berens 122). His name was so feared that it was never mentioned out loud by mortals. Whenever he was on earth in search of a victim, Pluto rode in a chariot of gold drawn by four coal-black steeds. Writing about Pluto's chariot, Ovid said, "Her [Proserpina's] captor sped his chariot and urged on his horses calling each by name and shaking the dark-dyed reins on their necks and manes" (95). Sometimes wearing a helmet specially made for him by the Cyclops, he carried either a two-pronged fork as his scepter or the keys to the Underworld. The helmet could give its wearer the power of invisibility. Sometimes used by both mortals and immortals, it was made available to Perseus in his battle against the Gorgon Medusa.

Cerberus & Charon

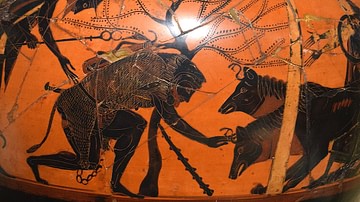

Getting into the Underworld was much easier than getting out – a feat deemed almost impossible. The entrance was guarded by Cerberus, a three-headed dog whose mouth dripped poison, who invoked fear in all who entered. However, not all who entered there were afraid when confronted by Cerberus. When the hate-filled Juno travelled into the Underworld to consult the Furies, "she made entrance there, and the threshold groaned beneath the weight of her sacred form. Cerberus reared up his threefold head and uttered his threefold baying. The goddess summoned the Furies, sisters born of Night, divinities deadly and implacable" (Ovid, 75). Hesiod in his Theogony writes: "A monstrous dog stands pitiless guard in front, with evil ways … lying in wait he eats up anyone he catches leaving by the gates …" (Hesiod, 48). Unlike an immortal, a mortal when facing his eternal fate, felt fear.

The spirit (sometimes called a shade) of a mortal who entered the Underworld must first confront the crossing of the river Styx, the river of darkness. The river Styx was one of the five rivers of the Underworld – the others being the Cocytus, composed of the tears of those condemned to hard labor in Tartarus; the Acheron, the river of sorrow and woe; the Lethe, which had the power to make one forget all unpleasant things and separated the Elysian Fields from the rest of the Underworld; and lastly, the Phlegethon, the river of fire that surrounded Tartarus.

Crossing the Styx was made in an old boat steered by the aged and "appallingly filthy" ferryman Charon. In his Aeneid, Virgil writes of the Trojan hero Aeneas, who travels into the Underworld to find his father and learn of his destiny. He is told by his guide Sibyl "… that ferryman is Charon: the ones he conveys have had burial. None may be taken across the bank to awesome bank of that harsh-voiced river until his bones are laid to rest" (139). To cross the Styx a spirit must pay the ferryman with a coin – an obolus – usually placed under the tongue of the deceased. Otherwise, the spirit must wander for 100 years before crossing. Although often seen as dark and forbidding, the Styx also has the power to impart invincibility – as seen with the Greek hero Achilles' near invulnerability.

Judgment of the Dead

Near Pluto's throne sat the three judges – Minos (former king of Crete), Rhadamanthus (his brother), and Aeacus – who questioned all souls, sorting out their earthly thoughts and actions, good and bad, and placing them on the scales of Themis, the blindfolded goddess of justice, whose trenchant sword makes her decisions "mercilessly" enforced. It was the duty of Minos to deliver the judge's decision. If good outweighed the bad, the spirit would go to the Elysian Fields, or if bad outweighed good, the spirit must suffer the fires of Tartarus – a dark and gloomy place of endless sorrow and incessant torment. In the Aeneid, while in the Underworld, Aeneas is faced with the sound of clanking chains and asks, "What kinds of criminals are these?" Sibyl replies that "No righteous soul may tread on the threshold of the damned ... Here Rhadamanthus rules, and most severe his rule is, trying and chastising wrongdoers, forcing confessions from any who, on earth, went gleefully undetected..." (146)

Furies, Fates & Gorgons

To assist in governing his realm, Pluto employed the Furies, Fates, and Gorgons. Guilty souls were entrusted to the Furies, who drove them through the gates of Tartarus. Visually terrifying, the three sisters – Alecto, Tisiphone, and Megaera – had snakes entwined in their hair with blood dripping from their eyes. Showing little mercy, they were used by Pluto "to chastise and torment those shades who during their earthy career had committed crimes" (Berens 139). They pursued and punished, among others, murderers and perjurers.

The three Fates (Parcae for the Romans or Moirai in Greek mythology) sat near Pluto's throne and determined the duration and direction of a person's life. Nona (Clotho) spun the thread of life, Decima (Lachesis) measured the thread, determining its length, while Morta (Atropos) used her scissors to cut the thread.

Lastly, there were the Gorgons who invoked great fear in all humans – Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa – "and were the personification of those benumbing and petrifying sensations that result from sudden and extreme fear" (Berens 146). They were winged monsters with hissing snakes around their heads. Any mortal who beheld them would be instantly turned into stone. Medusa, the only mortal, was killed by Perseus.

Tartarus

Tartarus has its share of notable sinners. Two made the mistake of disrespecting Juno. Tityus was a giant who insulted Juno – he was chained, like Prometheus – and a vulture ate at his liver. Ixion, the king of Lapithae, made the mistake of flirting with Juno. Jupiter was not pleased, so Ixion was bound to a constantly revolving wheel of fire. Tantalus, king of Corinth, deceived the gods. Atoning for his actions, he invited them to a banquet where he served his son, Pelops, killed and cooked. Sensing something was amiss, the gods refused to eat except for the grieving Ceres. She took a bite of what was his shoulder. The gods restored the boy to life – he received an ivory shoulder made by Vulcan (Hephaistos) at the request of Ceres. In Tartarus, he must stand in a pool of water beneath a tree of fruit. Thirsty, he stooped to drink but the water receded. Hungry, he reached for fruit but the branch swung upward. He is forever hungry and thirsty. Lastly, Sisyphus, another deceiver, was condemned to roll a huge stone up a hill, but before reaching the summit, the stone rolls down the hill. He must forever roll the stone but never reach the top.

Orpheus and Eurydice were in love but the young Eurydice died from a snake bite. Orpheus was heartbroken and vowed to go to the Underworld and retrieve his long love. Using his musical talents, he was able to soothe the three-headed guard dog Cerberus.

As he spoke thus, accompanying words with the music of his lyre, the bloodless spirits wept; Tantalus did not catch at the fleeing wave; Ixion's wheel stopped in wonder; the vultures did not pluck at the liver ... and you O Sisyphus, sat upon your stone. (Ovid 188)

Pluto allowed Orpheus to take his beloved and return to earth but with a warning not to turn around to see Eurydice or she will return to the Underworld. Orpheus did not heed the warning and lost her forever.

Worship & Legacy

There were no temples dedicated to Pluto, but there were altars. Conducted by a priest in black robes, sacrifices, usually made at night, consisted of black sheep or the occasional human. In medieval literature, Pluto appears in Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, presiding over the fourth circle of Hell. The largest dwarf planet – formerly considered the ninth planet – of the solar system, was named after Pluto, with its moons being Charon, Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra.