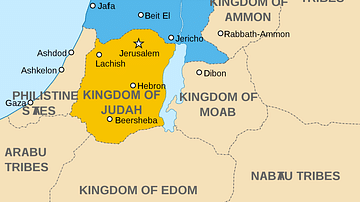

Though the kingdom of Judah was not particularly notable in terms of technological developments, technology, nonetheless, played a central role in its rise as a political power in the region. Emerging in the 10th century BCE, it reached its apex in the 7th century BCE, prior to its destruction around 586 BCE. Here, three aspects of technology provide insight into how and why Judah became a political power: town planning and urbanization, industry, and writing.

As ancient Judean technology here is presented primarily from the historical timeline as derived from archaeology, not the Hebrew Bible; the chronology suggested by Z. Herzog and L. Singer-Avitz will be used. Likewise, for the sake of this definition, 'Israel' and 'ancient Israel' refer to what is traditionally called the Northern Kingdom, while 'Judah' refers to what is traditionally called the Southern Kingdom, with reference to the Hebrew Bible. 'Israelite' and 'Judean' or 'Judahite' refer to the people of Israel and Judah respectively.

Town Planning & Urbanization

Archaeological remains attest to a rise in urbanization in the 10th century BCE as reflected in building technologies. Like Israelite sites, large administrative centers, complete with "massive fortifications, city gates, palaces, industrial and storage facilities, and [a clumping] of domestic houses" are developed in 10th-century BCE Judah (Dever, 304). Such structures allowed for Judeans to better defend themselves against external threats. Likewise, town planning and urbanization indicate centralized authority and management.

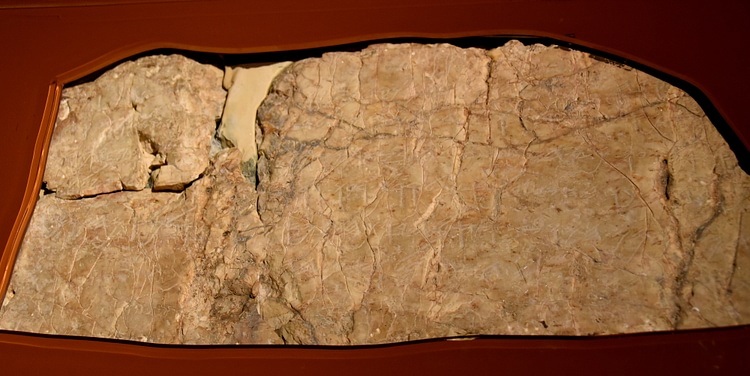

During the 9th and 8th centuries BCE, various water systems were built in Judah. For example, water tunnels dating to the 9th and 8th centuries BCE have been excavated at Beth-Shemesh, Beersheba, Kadesh-barnea, with the most notable one at Jerusalem. Between the 19th and 21st centuries CE, scholars excavated the Siloam Water System, a water system “comprised of various water-carrying subterranean tunnels and surfaces channels… located inside the assumed fortified walls of the City of David” (Guil 2017, 146), namely Jerusalem. In use from the Middle Bronze Age (17th century BCE) until the Hellenistic period (3rd century BCE), the Siloam Water System is often associated with Hezekiah's tunnel:

The other events of Hezekiah's reign, and all his exploits, and how he made the pool and the conduit and brought the water into the city, are recorded in the Annals of the Kings of Judah. (2 Kings 20:20)

Though scholars debate whether parts of the Siloam Water System dating to the Iron Age are precisely the work of Hezekiah's craftsmen, it is agreed that Jerusalem developed and used water systems between the 9th and 7th centuries BCE. Moreover, archaeological excavations have uncovered more developed defensive systems, large storage facilities, and administrative centers from the 9th and 8th centuries BCE, indicative of Judah's growing political power and centralization in the region. Many of these facilities were used into the 7th century BCE.

In the 7th century BCE, after the fall of the Israelite kingdom and the destruction of Samaria, Judah became an Assyrian vassal state, paying tribute to Assyria and functioning under their auspices. Likewise, Judah became a major producer of wheat during this period; however, there are no notable developments in building technology. In 586 BCE, after Babylon defeated Assyria, Jerusalem, and other major Judean cities were destroyed, effectively ending the era of the Judahite state.

Industry

Until the fall of Israel (Northern Kingdom) at the end of the 8th century BCE, Judah remained the underdog in comparison to Israel. Even so, archaeological records indicate significant changes during the 8th century BCE. During the 10th and 9th centuries BCE, Judeans used what is typically called red-slipped, hand-burnished pottery, with much variety. By contrast, pottery in the 8th century BCE was a lighter shade and more standardized, with less variety. Archaeologist Hayah Katz explains this as an industrial revolution. Whereas in the 10th–9th-century BCE pottery was manufactured on a small scale, pottery in the 8th century BCE was made with "wide-scale industrial production that required standardization" (Katz, 311). Though not the most exciting technology, pottery is indicative of Judah's increased socio-political centralization during the 8th century BCE. Such centralization may have enabled the subsequent growth of Judean grain production in the 7th century BCE.

After Assyria destroyed Israel around 700 BCE and ravaged Judah, many Judeans migrated towards the Beersheba Valley, which “could produce over 5,000 tons of grain a year” (Faust and Weiss, 75). Though the archaeological records are unclear concerning the precise technologies used in Judah to produce massive amounts of grain in the 7th century BCE, the migration and technologies associated with grain production enabled Judah to participate significantly in the regional economy. During the 7th century BCE, Philistine cities—like Ashkelon and Ekron—produced valuable commodities such as wine and olive oil. Judah participated in this system by producing grain primarily for itself. Surplus grain, though, was sold to the Philistine cities along the coast because they could not produce enough food. Simply put, Judah produced grain, using associated technologies, in order to participate in the local economy during the 7th century BCE.

Writing

Though often taken for granted, writing is, in fact, a technology:

Writing is a 'machine' to supplement both the fallible and limited nature of our memory (it stores information over time) and our bodies over space (it carries information over distances). (Writing as technology, Oxford University Press Blog).

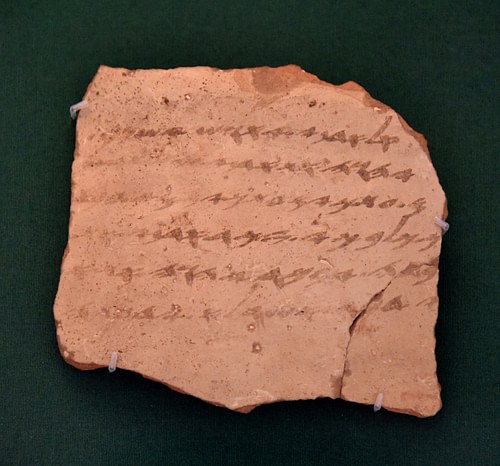

Thus, understanding the history of writing in ancient Judah is important for understanding technology history and the development of Judean social and economic classes. Evidence for writing in Judah comes from multiple sources outside of the Hebrew Bible. Two sources will be discussed here: “for the king” stamps and the Lachish letters.

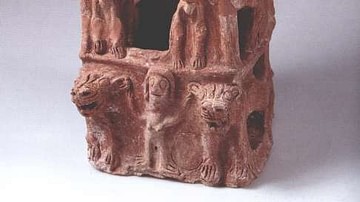

First, “for the king”, or lmlk, stamps (Hebrew לְמֶלֶך) are stamp impressions on pottery handles uncovered in late Iron Age Judah (8th century BCE). Stamps typically included a royal symbol (a four-winged scarab or a winged sun-disk) and a place name. The stamps signified that the agricultural item inside the vessel was from the royal estate. Currently, archaeologists know of about 2,000 jar handles with lmlk stamps. Furthermore, lmlk stamps first became common at “the beginning of the last third of the eighth century BCE, the period when Judah became a vassal kingdom” to Assyria (Lipschits, 345). Perhaps unsurprisingly, this is also when Judah began producing grain in the Beersheba Valley and Judean pottery became more standardized. Thus, the technology of writing is evidence of increasing power centralization in Judah beginning in the late 8th century BCE.

Conclusion

With the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BCE, the Judahite state ended. Fortunately, traces of the Judahite kingdom have been uncovered since the 19th century CE. By piecing together small pieces of archaeological evidence, we have a better picture of ancient Judahite history. In particular, we can better understand how common technologies like architecture, writing, pottery, and grain production enabled the Judahite kingdom to become a relatively significant power in the Levant.