Burial of the dead is the act of placing the corpse of a deceased person in a tomb constructed for that purpose or in a grave dug into the earth. Archaeological excavations have revealed Neanderthal graves dating back 130,000 years, marking burial as among the earliest human activities. Grave goods with the corpse suggest proper burial associated with an afterlife.

In cultures such as Mesopotamia, tombs and graves were cut into the ground in the expectation that the soul of the individual so buried would more easily reach the afterlife which was thought to exist underground. Graves in the cultures of the ancient world were usually marked by a stone bearing the person's likeness and name or by an elaborate tomb (such as the pyramids of Egypt or the tholos tombs of Greece) or megalithic stone dolmens, passage graves, and cairns such as those found in Scotland and Ireland.

Whatever kind of grave or tomb was constructed, however, the importance of the proper burial of the dead was emphasized by every ancient culture and the rites accompanying burial were among the most elaborate and significant in many ancient cultures. Burial of the dead in the ground has been traced back over 100,000 years of civilization as evidenced by the Grave of Qafzeh in Israel, a group tomb of 15 people buried in a cave along with their tools and other ritual artifacts. The earliest grave uncovered thus far in Europe is that of the Red Lady of Wales, dated at 29,000 years old, and, in the Near East, the Shanidar Cave in the Zagros Mountains, dated to between 60,000 and 45,000 years ago.

Burial Practices in Mesopotamia

Burial in Mesopotamia with recognizable grave goods began prior to c. 5000 BCE in ancient Sumer where food and tools were interred with the dead. According to the historian Will Durant, "The Sumerians believed in an after-life. But like the Greeks they pictured the other world as a dark abode of miserable shadows, to which all the dead descended indiscriminately” and that the land of the dead was beneath the earth (128). Because of this, it seems, graves were constructed in the ground to provide the deceased with easier access to the netherworld.

Throughout Mesopotamia, those who were not royalty were buried below the family home or next to it so that the grave could be regularly maintained. If a person was not buried properly they could return as a ghost to haunt the living. Ghosts in ancient Mesopotamia were understood as just another aspect of life and their appearance, though often unwelcome was recognized as a haunting for some purpose.

This haunting could take the form familiar from popular ghost stories or films where a disembodied spirit causes problems in the home or, more seriously, as a form of possession in which the spirit entered into the individual through the ear and wreaked havoc on one's personal life and health. In either case, one of the most common causes for the return of the dead was an improper burial.

Cremation was uncommon throughout Mesopotamia owing to the scarcity of wood but, even if fuel for a fire had been available, the Mesopotamians believed that the proper place for the souls of the dead was in the netherworld of the goddess Ereshkigal and not in the realm of the gods. If one were cremated, it was thought, one's soul ascended skyward toward the home of the gods and, as a human soul, would not be at home there. It was far more fitting for one's soul to descend to the underworld with other human souls. In ancient Sumer, as in later Babylonia and, more or less, throughout Mesopotamian history, it was believed that the dead “went to a dark and shadowy realm within the bowels of the earth, and none of them saw the light again” (Durant, 240). In Babylonia, the dead were buried in vaults, although, as Durant notes:

A few were cremated and their remains were preserved in urns. The dead body was not embalmed, but professional mourners washed and perfumed it, clad it presentably, painted its cheeks, darkened its eyelids, put rings upon its fingers, and provided it with a change of linen. (240)

This burial process would be developed further by the Egyptians although whether their practices derived from those of Mesopotamia or developed independently is still debated.

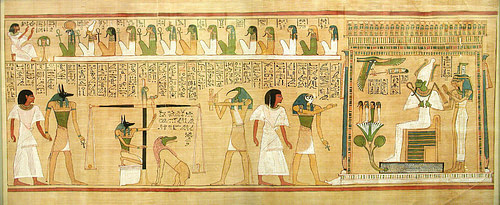

Burial in Egypt

In Egypt, the dead were also buried underground and, famously, in the pyramids of such as those at Giza. Durant writes:

The pyramids were tombs, lineally descended from the most primitive of burial mounds. Apparently the Pharaoh believed, like any commoner among his people, that every living body was inhabited by a [spirit] which need not die with the breath…The pyramid, by its height, its form and its position, sought stability as a means of deathlessness. (148)

For most Egyptians, however, a grave in the earth was the usual final resting place. The deceased would be buried with grave goods and as many shabti dolls as a family could afford to help with chores in the afterlife. Egyptian burial practices extended to one's pets and Herodotus has recorded how, in an Egyptian home that has lost a cat, the family would shave their eyebrows and observe a period of mourning on par with the death of a human being. Cats were mummified as were dogs and other pets (such as baboons, gazelles, birds, fish) and rituals observed at their passing.

The Egyptian tradition among royalty of creating great monuments and tombs inscribed with their deeds was observed to make sure the ruler would not be forgotten by the living and so would continue to exist on earth even after death. To erase one's memory on earth was to erase one's immortality and this is why Thutmose III, who vandalized the public statuary of Queen Hatshepsut, left those monuments to her which were out of the public eye untouched. He may have wanted to discourage other women from following Hatshepsut's example in the future but did not wish to condemn her to non-existence by removing all trace of her name and deeds.

Burial Rituals in Greece

Ancient Greece also employed burial under the earth and, as previously noted by Durant, continued the tradition of the afterlife existing below the ground. The ancient Greeks (perhaps following an Egyptian tradition) made sure to provide their dead with carefully carved stones to remind the living of who the deceased were and what honors were still due them. Remembrance of the dead was a very important civic and religious duty, not simply a personal concern, and was dictated according to the concept of eusebia which, though frequently translated into English as 'piety', was much closer to 'civic duty' or 'social obligation'.

Eusebia dictated how one should interact with one's social superiors, how the youth treated their elders, how masters interacted with slaves, and how husbands treated their wives. It also extended, though elevated to the concept of housia (holiness) to one's relationship with the gods. Different Greek city-states observed their own particular burial rites but the one aspect they all had in common was the continued remembrance of the dead and, especially, their names.

Sons were named for their father's father and daughters for their mother's mother in order to preserve the memory of that individual (to take one example, Aristotle's son, Nichomachus, was named for Aristotle's father). Whether buried in an elaborate tomb or in a simple grave, the Greeks maintained that the dead must continually be remembered and respected in order for their souls to continue to exist in the afterlife.

Maya Burial Rituals

The Maya viewed life after death as a dismal world fraught with peril and darkness and their burial rites centered on directing the soul in the right path toward freedom from the underworld. The dead were buried with maize placed in their mouth as a symbol of the rebirth of their soul and also as nourishment for the soul's journey through the dark lands of Xibalba, the netherworld, also known as Metnal.

Bodies were positioned in graves underground, as in Mesopotamia, to allow easy access to Xibalba and were aligned in accordance with the directions of the Maya paradise (north or west). As the color red was associated with death, corpses were sprinkled with the shavings of the red mineral cinnabar and were then wrapped in cotton for burial. The Maya afterlife was a terrifying place of demons that could as easily harm one as help in the soul's journey toward paradise and perhaps the cinnabar was thought to disguise the soul as one of these infernal spirits and so aid the individual in their journey through the afterlife.

Everyone who died descended into the darkness of Xibalba except for those who died in childbirth, in battle, in sacrifice, or by suicide. Sacrifice included death incurred during the play of the ball game Pok-a-Tok, considered the game of the gods. However one died, the rites of burial were more or less the same except, of course, for kings and nobility.

Burial Rites in India

In ancient India, as throughout India's history, cremation was the usual practice in caring for the dead. Durant writes:

In Buddha's days, the Zoroastrian exposure of the corpse to birds of prey was the usual mode of departure; but persons of distinction were burned, after death, on a pyre, and their ashes were buried under a top or stupa – i.e. a memorial shrine. In later days cremation became the privilege of every man; each night one might see fagots being brought together for the burning of the dead. (501)

Even so, that was not the only means by which the dead were sent on to the next realm. It is also recorded that the elderly would often choose to have themselves rowed out into the middle of the Ganges River where they would then fling themselves into the sacred water and be swept away. Most people, though, were cremated and their ashes then strewn in the waters of the Ganges, thought to be the source of all life.

Depending on one's actions, beliefs, and behavior in life, the soul then rose to join with the Oversoul (the Atman) or descended back to the earthly plane in another incarnation. According to Hindu belief, the soul would continue to take on as many bodies in as many lifetimes as necessary to finally free one's self from the cycle of rebirth and death; a belief also held by adherents of Jainism and Buddhism.

Roman Burial Customs

According to Durant, “Suicide under certain conditions has always found more approval in the East than in the West” but, as in India and with the Maya, the Romans also approved of those who killed themselves as they believed it was preferable to disgrace and dishonor. The Roman belief in the continual presence of one's ancestors in one's life encouraged the practice of taking one's life in order to prevent shame attaching itself to the family name. There was, therefore, no difference, in pre-Christian Rome, in the burial of a suicide and one who died by other means.

Roman burial practices always took place at night in order to prevent the disruption of the daily activities of the city. A funeral procession began in the city and ended outside the walls at the cemetery. In order to maintain the boundary between the living and the dead (and also, no doubt, simply for health concerns) no one could be buried inside the city. The corpse was then either burned, and the ashes gathered in an urn, or placed in a grave or tomb.

Chinese Burial Rites

This same understanding of funerary rites informed mortuary rituals in China. Chinese burial practice, no matter what era or dynasty, was conducted in accordance with strictly observed ceremonies to ensure the passage of the spirit to the other realm. Burial, as in other cultures, included the placement of personal property in the tomb or grave of the deceased as an important aspect of the funerary rites. The particular items interred with the dead changed with dynasties and the passage of time but the belief in an afterlife which was very much like earthly existence (similar to the Egyptian concept in many ways) maintained that the dead would need their favorite objects, as well as things of value, in the other world.

According to The British Museum, “Chinese burial practices had two main components: tombs and their contents, and ceremonies to honour the dead, performed in temples and offering halls by their relatives.” The tomb of the first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huangdi, is the most famous example of Chinese burial practices in the ancient world. Shi Huangdi's tomb was designed to symbolize the realm he presided over in life and included all he would need in the next - including a terracotta army of over 8,000 men - and the rites observed at his funeral were elaborate versions of those common throughout China.

Burial in Scotland & Ireland

Burial practices in Scotland and Ireland were remarkably similar early on in that both cultures built cairns, dolmens, and passage graves to house their dead. It is not known what precise rites were performed at the funerals in ancient Scotland or Ireland because there is no written record of these proceedings. It seems that burial in cairns dates to at least 4000 BCE while burial in graves becomes more common c. 2000 BCE. Wooden coffins also appear in the 2000 BCE range along with personal possessions buried with the dead.

As so many cairns were looted through the centuries, whatever may have been interred in burial has long ago been carried away. Some, however, like the famous dolmen of Poulnabrone (County Clare, Ireland) still had enough grave goods and remains for archaeologists to be able to positively identify it as an important burial site. The Neolithic site of Clava Cairns (Inverness, Scotland) is another example of an intact burial site which also seems to have served astronomical purposes.

More modest graves, which held the dead in coffins or sarcophagi, were more often overlooked by looters and so their contents remain better preserved. In these cultures, as in the others, a belief in the continued existence of the soul after death prevailed and, while their precise rites are not known, they most probably were similar to those of other cultures and included prayers and supplications to higher powers for aid in the journey of the deceased. Although there is no written record of a belief in the afterlife from these cultures, the cairns, dolmens, and passage graves themselves attest to this belief in their construction and orientation with astrological directions and events.

With the coming of Christianity to Ireland and then Scotland, the burial rites became Christianized and are known through the written record. Although Christ was then addressed as the higher power that would comfort and lead the dead toward the afterlife, it is thought that this deity simply replaced the older, pagan, god who would have been featured in the rituals. This same process of the 'Christianizing' of older burial rituals and rites took place in every culture where Christianity established itself and, most notably, in Rome. It was the city of Rome from which the Catholic traditions concerning burial originated and developed into the most common customs surrounding modern-day burials, whether secular or religious, in the west.