The Ginkakuji Temple in Kyoto, Japan, formally referred to as Jisho-ji and otherwise known as 'The Serene Temple of the Silver Pavilion', was first built in the 15th century CE. It is a Rinzai Zen temple with the complex consisting of the Hondo Hall, Togudo Hall, Silver Pavilion, landscape gardens, and a pond garden. The Togudo Hall includes the oldest surviving tea ceremony room in Japan. Ginkakuji was designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 1994 CE and is an official National Treasure of Japan.

Ashikaga Yoshimasa

Work began on the temple in 1460 CE and, after a temporary break during the Onin War (1467-1477 CE), resumed after 1480 CE to be completed in 1483 CE. The temple, located in the Higashiyama area of north-east Kyoto (then called Heiankyo), was conceived as a counterpart to the Kinkakuji or Golden Pavilion temple on the other side of Kyoto, first built in 1397 CE. Its original purpose was to function as the retirement estate for the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa (l. 1436-1490 CE, r. 1449-1474 CE). The grounds, designed by the famed landscape gardener Soami, were massive, some 30 times bigger than the site today and including 30 pavilions.

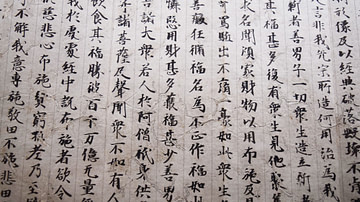

Following Ashikaga Yoshimasa's death in 1490 CE, the complex was converted into a Zen temple. The complex had already gained a reputation as a great centre of the arts and culture, especially such quintessential Japanese activities as flower arranging, Noh theatre, ink painting, the study and appreciation of fine porcelain and lacquerware, landscape gardening, and the tea ceremony. Ashikaga Yoshimasa even had a catalogue drawn up by his resident expert No-ami, the Kundai-kwan Sayuchoki, which offers commentaries on particularly fine pieces of Japanese and Chinese artworks in the shogun's impressive collection at Ginkakuji. The catalogue also provides handy tips such as how to tell if articles are genuine or fake and what exactly the correct and most aesthetically pleasing position is for tea paraphernalia on a room's shelving. The catalogue was used by art connoisseurs for generations after the shogun's death. As for the complex, today, only the Silver Pavilion and Togudo Hall survive intact from the original 15th-century CE estate.

The Silver Pavilion

The Silver Pavilion is situated in a masterpiece of landscape gardening which deliberately offers walkers a brief glimpse of the building before taking them away through tall hedges via a circuitous path to a raised viewpoint from which they then look down upon the pavilion in all its glory. The two-storey wooden pavilion was originally designed as a place for moon-viewing, hence its orientation to the east and the rising moon. Gazing at the moon, a symbol of enlightenment in Buddhism, was a common practice amongst the Japanese elite in medieval times when parties were organised for that purpose, and sake was drunk and poetry recited.

The pavilion, despite its common name, is strangely lacking in silver decoration - in marked contrast to the Golden Pavilion of Kinkakuji. It may be that the original plan to use silver proved too expensive or it is possible that the silver effect comes from the moonlight shining on the lacquered exterior. Certainly, Ashikaga Yoshimasa was very preoccupied with the beauties of the moon and its effect on his retreat. Indeed, it is the subject of one of the shogun's most famous poems:

My lodge lies at the foot

Of the Moon-Awaiting Hill

The shortening hill shadow

As it finally disappears

Almost fills me with regret.

(quoted in Dougill, 2017, p118)

The effect of moonlight on the pavilion is enhanced by the reflection offered by the Mirror Pond next to which the pavilion stands. Indeed, the function of the pond was precisely to see the moon's reflection from the second floor of the pavilion once it had risen out of view from the first floor. The pond also has waterfalls and small islands for cranes and turtles, both symbols of good fortune.

The ground floor of the pavilion, called the Shinkudan or 'Empty-Heart Hall', is built in the residential style. In contrast, the upper floor is typical of Zen architecture with its bell-shaped windows. The roof is made using overlapping shingles of Japanese cypress, with each individual piece secured by a bamboo nail. Inside the pavilion are many examples of Japanese religious statuary and paintings, including a total of 1,000 images of Jizo, the Buddhist guardian of the afterlife. The upper floor contains images of Kannon, the Bodhisattva of compassion, with one fine statue set in a small artificial grotto.

The Togudo Hall

The rectangular Togudo Hall was built in 1486 CE as the private residence of Ashikaga Yoshimasa. Inside is a chapel with separate rooms for study, incense guessing (another favourite Japanese pastime), and one for the tea ceremony. This tearoom, the Dojinsai, has space for only four or five people and has a square sunken firebox in the flooring. It is the oldest surviving example of a tea ceremony room in Japan. The roof is thatched while the rooms inside, with their tatami mat flooring, paper windows, alcoves and irregular shelving, are the oldest surviving examples of the traditional residential architecture of Japan, shoin-zukuri. There is, too, a veranda from which to view the adjacent gardens and a spring-fed pond which has seven small stone bridges. The gardens are dotted with boulders of various sizes, and these were each donated by supporters of Ashikaga Yoshimasa and his feudal lords in the typical Japanese tradition. Stones were selected for their aesthetic qualities, and each has its own particular name and history.

The Hondo Hall

The Hondo is the main hall of the complex; it was reconstructed in 2005 CE. Inside there are 17th-century CE screen paintings (fusuma), amongst them works by such celebrated Japanese artists as Yosa Buson (1716-1784 CE) and Ike no Taiga (1723-1776 CE).

The Gardens

The gardens of Ginkakuji have many features which are designed to replicate famous scenes from nature and Japanese literature. One of the highlights of the gardens is the romantically named Sea of Silvery Sand (Ginsha-nada) which replicates the outline of the West Lake in China. The sand is meticulously raked in an art form known as samon so that in moonlight its ridges appear as ripples in water. By the sea of sand is a two-metre high mound which is officially a small lunar viewing platform (Kogetsudai) but in which many have seen a likeness to Mount Fuji or have taken as a representation of the sacred Buddhist mountain Sumeru. Still others consider the mound a harmonious addition to the sea of sand which represents the balance of yin and yang, with yin here being the horizontal sea and yang being the vertical mound. Whatever its precise purpose, the mound of sand is meticulously remade each month to keep its precise and smooth form.

Additional areas of the garden include a bamboo grove, a section with a variety of mosses and woods of black pines. Finally, the tomb of the complex's founder is on the site in a small building within which is a dark wood sculpture of the seated shogun wearing the robes of a priest. Ashikaga Yoshimasa may not have had a very brilliant political career but his patronage of the arts and lasting influence on the culture of medieval Japan, along with the magnificent Ginkakuji temple, are his great undisputed legacy.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.