Dated to the 7th century BCE, the Arslan Tash Amulet (AT1) was discovered in Arslan Tash, Syria and contains the writing of Phoenician, magic incantations. The limestone plaque includes a variety of features: incantations perceived to prevent demons from entering the household; reliance on Assur, Baal, Horon, the pantheon, and Heaven and Earth to enforce the incantation; and an incantation as a sort of covenant. These elements of the incantation are parallel to other texts throughout the ancient Near East, many of which are not incantations or magic texts. In what follows, each of these aspects will be further described.

Discovery & Description

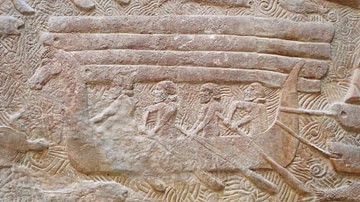

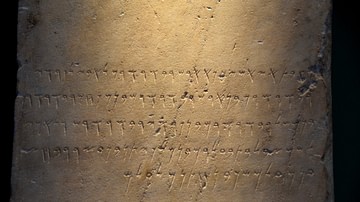

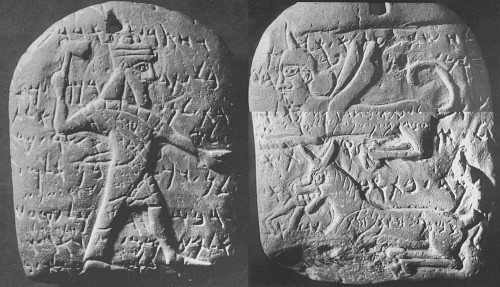

In 1933 CE, the Arslan Tash plaque was purchased in Syria from a villager in Arslan Tash (ancient Hadattu) in northeastern Syria. Measuring 8.2 x 6.7 cm, the tablet is by no means large. Three images are on the front of the tablet: “a winged sphinx with a pointed helmet, a recumbent wolf with the tail of a scorpion, and a small human figure being devoured by the wolf creature” (Haberl Unpublished). The other side of the plaque “depicts a striding warrior figure, wielding a double axe and dressed in a short tunic and Assyrian long coat” (ibid). There is also a hole drilled in the top of the tablet.

Around these images is an incantation, written in a Phoenician dialect and script. The first incantation begins with a speaker addressing two demons and noting the divine sponsor of the tablet (lines 1-5). Those who are not permitted to enter the house include the Fliers and the Stranglers – types of demons; Sasam, son of Pidrišiša, is a god and the lord of the incantation, providing the incantation with power and authority. Subsequently, the speaker demands that where the speaker enters, the demons and deities do not enter (lines 5-6). Then, the speaker employs his/her covenant with the pantheon and cosmos (Heaven and Earth) as a means of legitimizing the incantation, perceiving the pantheon and cosmos to enforce the imperatives against the demons (lines 7-18). Three shorter, subsequent incantations are written atop the three images on the tablet.

Unfortunately, little is known about the provenance of the incantation or who the scribe is. And though the authenticity of the Arslan Tash amulet has been questioned in the past, most scholars accept its authenticity now. The plaque is currently stored in the Museum of Aleppo, Syria.

The Arslan Tash Incantation (AT1)

Whispering-incantation against the Flying-one,

the oath of Sasam, son of Pidrišiša, god,

and against the Strangler of the lamb:

“The house I enter, you shall not enter

And the court I tread, you shall not tread!

He has made an eternal contract with us.

Assur made a pact with us, all the sons of El,

, and the great council of all the holy ones,

With the oath of heaven and earth

With the oath of Baal, lord of the earth

With the oath of Horon, whose utterance is true,

His seven concubines and the eight wives of Baal Qudš”

[Written around and between the images]Oh Flying one, from the dark room pass away!

Now! Now, night demons!

[Written on the Sphinx figure]From my house, O crushers, go away!

[Written on the wolf-like figure]Oh Sasam, let it not be opened for him

And let him not come down to the door-posts

The sun is rising for Sasam.

Disappear, and fly away home.

[Written on the axe-wielding figure]

(modified from Cross and Saley 1970 and Berlejung 2010).

Deities & Demons in the Incantation

A variety of demons and deities appear throughout the incantation. In what follows, each demon and deity will briefly be discussed.

Fliers & Stranglers – Undoubtedly, the Fliers and Stranglers refers to “personified female evil forces, who preferably attack children” (Berlejung 2010). As such, they are akin to the Mesopotamian Lamashtu.

Sasam – Though many scholars have argued that Sasam is a demon, it is more likely that Sasam is a deity with Cypriot-Phoenician or Hurrian origins. It is most likely a deity because Sasam appears in personal names; this is rarely the case with demons. Moreover, Sasam appears in a Phoenician amulet, intended to bring “blessing and protection by means of writing a god's name on it” (Berlejung 2010). As such, though one of many opinions, it is preferable to view the phrase “Sasam, son of Pidrišiša” as referring to “the one who formulates… the performative defense charm… and who intervenes in favor of humans” (Berlejung 2010).

Assur – Mention of Assur as the guarantor of the oath, that is the one who enforces the incantation which is expressed through an oath, is not surprising in light of the political and religious situation during the 7th century BCE when Northern Syria was under the control of the Neo-Assyrian empire. Furthermore, according to an ancient Near Eastern treaty between Esarhaddon and all his vassal states, establishing an oath with any deities was punishable by death: “You shall not take a mutually binding oath with (any)one who produces (statues of) gods in order to conclude a treaty before gods” (SAA 2: 6, §13). With Assur as the guarantor of the oath, though, the amulet affirms the centrality of Assyria and its respective religious devotions in the 7th century BCE. Thus, the Arslan Tash amulet does not oppose the Neo-Assyrian empire but affirms it.

Sons of El & Council of the Holy Ones – The deities indicated by the phrases “Sons of El” and “Council of the Holy Ones” essentially mean the entire divine pantheon, headed by the Assyrian deity Assur. Similar notions of a head deity with a divine pantheon are present in ancient Israelite texts like Psalm 82, Ugaritic texts like the Tale of Aqhat, Mesopotamian texts like Enuma Elish, and various Phoenician and Aramaic inscriptions. In other words, although pantheons were headed by different gods or goddesses in different time periods and regions, the notion of a divine pantheon was common throughout the ancient Near East.

Heaven & Earth – Though heaven and earth are not necessarily deities or demons in this amulet, they regularly have the agency to act as witnesses with regard to events, promises, or oaths throughout Sumerian, Hittite, and Ugaritic texts. In a few Ugaritic texts, for example, Heaven and Earth are deified, capable of receiving offerings. Moreover, Heaven and Earth appear in Ugaritic texts as witnesses to oaths, just as in the Arslan Tash amulet.

Baal – Baal is a common deity throughout Northern Syria, often distinguished regionally through different titles. These include, though are not limited to, Baal of Tyre, Baal Shamem, and Baal Saphon. It is unclear exactly which form of Baal is referenced in the amulet.

Horon / Baal Qudš – In Ugaritic and Egyptian texts, Horon is a deity associated with demons. Ironically, he is invoked at Ugarit both as a chief of demons and as a deity who works against demons. In the Arslan Tash amulet, he is invoked as a demon who works against demons. As for Baal Qudš, some scholars have suggested that it is another name for the deity Horon.

Incantation as Treaty

Central to the Arslan Tash amulet is the notion of an oath or covenant between the individual who created and utilizes the amulet and the various deities who ensure that the incantation is effective, such as Sasam, Assur, the divine pantheon, Horon, and Baal. Conceptually, the hierarchy of power is as follows: deities > demons > humans. In order to prevent demons from attacking and killing humans, then, humans must create a sort of covenant with the deities. In doing so, the hierarchy changes because the deities now protect the humans: deities (with humans) > demons. By calling upon the deities in terms of an oath, they are charged with ensuring that the incantation is effective.

While the Arslan Tash amulet employs covenant, or oath, language uniquely as an incantation, it draws from the more common language of oaths, treaties, and covenants as they concern the relationship between a more powerful entity and a less powerful entity. In Neo-Assyria, for example, these treaties are called adê-treaties. Jacob Lauinger, professor at Johns Hopkins University, defines an adê as “an obligatory behavior that was imposed on an individual or group of individuals and transformed into a destiny by projecting it into the divine realm” (Lauinger 2015).

In the Arslan Tash amulet, Sasam places obligations upon the demons, the Fliers and the Stranglers, not to enter the household. Through establishing an oath (i.e. treaty or covenant) with Assur and the pantheon, Sasam effectively invokes their respective powers. The divine powers of Assur and the pantheon become the things which prevent demons from transgressing the obligatory behavior imposed by Sasam upon the demons.

A similar notion of treaty is expressed in the Hebrew Bible. For example, in Exodus 19:4, Yahweh speaks to Israel: “Surely you have seen what I did to the Egyptians! I carried you upon the wings of eagles and I brought you to myself.” Yahweh's saving act becomes the foundation for a treaty, more commonly translated as a 'covenant', that he obligates the people follow: “So, if you actually obey my voice and keep my covenant, then you will be my possession from among all the peoples of the earth” (Exodus 19:5). Like with the Arslan Tash amulet and the Neo-Assyrian adê-treaties, Yahweh does not offer the people a choice; rather, Yahweh imposes an obligation upon the people to obey Yahweh. A similar notion is expressed in Psalm 78, wherein the covenant is not a mutual agreement or relationship; rather, it is a covenant “as the commitment or obligation God lays on them,” namely the Israelites (Goldingay 2007).

In summary, then, the Arslan Tash amulet exemplifies how people used political language in a religious way. The author employed the same models as found in cuneiform source, the Hebrew Bible, and Aramaic source (see the Sefire Treaty), namely obligations imposed against individuals and groups. By leveraging political and religious language, the Arslan Tash amulet reframes politically charged language for its own social and religious goals, placing obligations on evil demons instead of population groups.

Target of the Incantation

As already stated, the incantation is against the set of female demons: the Fliers and the Stranglers of Lambs. Scholars tend to interpret these demons as beings perceived to enter homes and kill children. By leveraging the power of Assur, with whom the oath against the demons is made, the demons are perceived as being unable to enter the household and kill children.

It is equally plausible that the incantation was intended to prevent the death of animals as well, as suggested by the demon called “The Strangler of Lambs.” Throughout the ancient Levant, livestock was often kept in the courtyards of houses, commonly interpreted as the central public space. It is also the location which the demons are obligated to stay out of. Moreover, Horon is one of the deities called upon to enforce the obligation. Importantly, Egyptian incantations also call upon Horon, who prevents wolves from killing livestock. As such, it is notable that one of the demons drawn onto the amulet is a wolf-like figure. The Egyptian role of Horon plausibly indicates an association between Horon and the image of a wolf-like demon. Taken together, these points suggest that the incantation may have also been intended to prevent demons from killing livestock who were housed in the courtyard of the household.

Location of the Amulet in the Household

Although the Arslan Tash amulet is not associated within a particular archaeological site, most scholars agree that it was designed to hang over a door, at the entrance into a household. This is especially clear in the final incantation: “And let him not come down to the door-posts.” Likewise, a hole drilled into the top of the amulet suggests it was meant to be hung upon a wall. Notably, the Arslan Tash amulet is not unique in its concern with placing apotropaic materials at the entrance of a household. Apotropaic means something which has the power to avert evil. As several scholars have noted, this is a practice attested in other Phoenician texts and in the Hebrew Bible.

In Deuteronomy 6, for example, Moses declares one of the central tenants of modern Judaism, the Shema. Verse 9 is particularly notable: “And you shall write [the words of the covenant] upon the doorposts of your household and upon your gates.” The Hebrew word for “doorposts” is the same as the Phoenician word for “doorposts.”

Likewise, in the Biblical narrative about the Hebrew exodus out of Egypt and the Passover, Yahweh commands the people to take from the blood of the sacrificed lamb and place it upon the doorposts of the household (Exodus 12:7). The blood has an apotropaic function, inasmuch as it serves as a sign that Yahweh should pass over those particular households. In other words, Yahweh promises not to slay the firstborn of those households with the blood on the doorpost (Exodus 12:13).

What both examples show, then, is that putting apotropaic materials on the entrance to a household was not uncommon throughout the Levant; rather, it was a common practice in order to ward off unwanted evil or negative influences, albeit being expressed in ways unique relative to their respective social, religious, and cultural norms and situations.

Conclusion

The precise meaning of the Arslan Tash inscription is a hotly debated subject. As such, this description attempted to focus on the more commonly accepted interpretations and implications of the Arslan Tash amulet. First, we provided an overview of all the demons and deities in the amulet, one of the more debated aspects of the amulet. Second, we considered how the magical incantation employed contemporary political language for particular social and religious goals, challenging the idea that ancient Near Eastern civilizations placed a strong distinction between the political and religious spheres. Third, we considered how the amulet functioned within a household at the doorposts, showing how the idea of placing apotropaic materials at the doorpost was part of a broader ancient phenomenon. At base, then, the Arslan Tash amulet illustrates how ancient people used magic in a unique way that drew from common elements throughout the ancient world.