Ancient Persian Religion was a polytheistic faith which corresponds roughly to what is known today as ancient Persian mythology. It first developed in the region known as Greater Iran (the Caucasus, Central Asia, South Asia, and West Asia) but became focused in the area now known as Iran at some point around the 3rd millennium BCE.

This region was already inhabited by the Elamites and the people of Susiana whose beliefs are thought to have influenced the later development of Persian religion. The Persians arrived as part of a large-scale migration which included a number of other tribes who referred to themselves as Aryans (denoting a class of people, not a race, and essentially meaning “free” or “noble”) and included Alans, Bactrians, Medes, Parthians, Scythians, and others. The Persians settled near the Elamites in Persis (also given as Parsa, modern Fars), which is where their name comes from, and religious rituals were instituted shortly after.

How the early Persians worshipped their gods is unknown except that it involved fire and outdoor altars. It is thought to have resembled modern-day Zoroastrian rites in many respects. Inscriptions from the Achaemenid Persian Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) reference the kings' religious beliefs – which may have been the early polytheistic faith or the later Zoroastrian monotheism – and religion continued to play a central role in the later Parthian Empire (247 BCE-224 CE) and, to a much greater degree, in the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) which made Zoroastrianism the state religion.

When the Sassanian Empire fell to the invading Muslim Arabs in 651 CE, Persian religion was suppressed and adherents either converted, left the region, or continued the faith in secret. Zoroastrianism survived the conversion efforts, however, and is still practiced in the modern day while the early polytheistic faith was relegated to myth and lore. The present-day religion known as the Baha'i Faith, often referenced as a “Persian religion”, developed from an Islamic sect known as Babism and has no direct historical connection to the religious systems of ancient Persia.

The Early Faith

The polytheistic faith of the Persians was centered on the clash of positive, bright forces, which maintained order, and negative, dark energies that encouraged chaos and strife. The Persian pantheon was presided over by Ahura Mazda, the all-good, all-powerful creator and sustainer of life, who gave birth to the other gods. Ahura Mazda created the world in seven steps beginning with sky (though in some versions it was water). The purpose, it seems, was the manifestation of universal harmony, but this was thwarted by the evil spirit of Angra Mainyu, Ahura Mazda's cosmic opponent.

The sky was created first as an orb that could hold water, and the waters were then separated from each other by earth, which was planted with vegetation. Once this was done, Ahura Mazda created the Primordial Bull, Gavaevodata, who was soon after killed by Angra Mainyu (also known as Ahriman). Gavaevodata's corpse was carried to the moon and its seed purified and, through its death, it then gave birth to all other animals.

The first human was then created, Gayomartan (also given as Gayomard, Kiyumars), who was so beautiful that Angra Mainyu had to kill him. His seed was purified in the ground by the sun, and from it grew a rhubarb plant, which became the first mortal couple – Mashya and Mashyanag. Ahura Mazda gave them souls through his breath and they lived in harmony with each other and the world until Angra Mainyu whispered to them that he was their true creator and Ahura Mazda was the deceiver. The couple believed this lie and fell from grace, afterwards left to live in a world of disorder and strife.

They could choose to live well, even under these conditions, by adhering to the truth of Ahura Mazda and turning away from the enticements of Angra Mainyu. This conflict between Supreme Good and Ultimate Evil was the heart of the early religion and almost all the supernatural entities associated with the faith fell on one side or the other (the exceptions being genies and faeries) with humans also forced to make the same choice. The earliest vision of life-after-death was of a dark realm of shadow which the soul moved through, its existence dependant on the prayers and memory of the living, until it crossed a dark river where good souls were separated from the bad.

Later - possibly before Zoroaster but probably after - the afterlife was reimagined to include a final judgment on the Chinvat Bridge (the span between the living and the dead), one's actions weighed in a celestial balance, and the concept of heaven and hell. If one chose the path of truth, one would live well and, after death, find paradise in the House of Song; if one chose to listen to Angra Mainyu, one would live with strife, confusion, and darkness, and, in the afterlife, would be dropped into the hell known as the House of Lies.

The soul Ahura Mazda had breathed into the first couple was immortal and, as a gift, needed to be cared for. Ahura Mazda provided the people with everything they needed and only wanted one thing in return: that they care for their souls by listening to his counsel and defending the values he stood for. The meaning of human existence, then, was making the choice to honor that gift or repudiate it through a selfish and willful adherence to Angra Mainyu and his pretty, but ultimately false, promises.

Humans had been given free will and each person had to choose, on their own, which path to follow and how to live a life. To assist people in making the right choice, as well as protect them from the dark forces, Ahura Mazda created the rest of the pantheon of the gods and, among the most popular, were:

- Mithra – god of the rising sun, covenants, and contracts

- Hvar Ksata – god of the full sun

- Ardvi Sura Anahita – goddess of fertility, health, water, wisdom and sometimes war

- Rashnu – an angel; the righteous judge of the dead

- Verethragna – the warrior god who fights against evil

- Vayu – god of the wind who chases away evil spirits

- Tiri and Tishtrya – gods of agriculture and rainfall

- Atar – god of the divine element of fire; personification of fire

- Haoma – god of the harvest, health, strength, vitality; personification of the plant of the same name whose juices brought enlightenment

Rituals centered on the four elements, starting with fire (which was kindled on an outdoor altar) and ending with water (which was honored as a life-giving element) in the presence of air and standing on the earth. The four cardinal points were also acknowledged. There were no temples in early Persian religion just as there were none later in Zoroastrianism because it was believed the gods were everywhere and immanent and no building could or should contain them.

Fire was central to the faith in symbolizing divinity - the actual presence of the god Atar - but earth, air, and water were also deeply respected as sacred emanations from the supreme god. Although the Greeks claimed the Persians worshipped fire and the elements, this is not true; they worshipped the divine power who created the elements.

Zoroaster

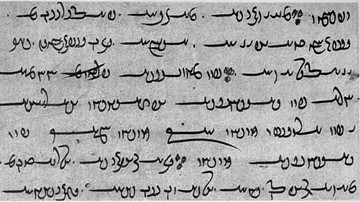

The ancient Persian religion was an oral tradition – it had no written scripture – and so all that is known of it in the present day comes from works written after the revelation of the prophet Zoroaster (also given as Zarathustra) between c. 1500-1000 BCE. It seems that the veneration of many gods extended to worship of one's ancestors, and a priestly class (later known as the magi) officiated at rituals and recited whatever sacred texts were required. Although there was no temple, there was a religious bureaucracy and hierarchy with a chief priest and lesser priests to whom people brought offerings in return for prayers and healing.

The priestly class was among the highest of the Persian social system and were wealthy enough to be able to offer significant loans on which they received interest. There was also, no doubt, a market for statuettes and amulets of various gods or entities worn for protection just as there was in Mesopotamia and Egypt. It is no surprise, therefore, that when religious reform was first suggested, it was not received well by the clergy.

Vohu Manah was a direct representative of the One True God, Ahura Mazda, who revealed to Zoroaster that the earlier understanding of religion as practiced by the magi was incorrect. There was only one god, Ahura Mazda, and Zoroaster would be his prophet.

Zoroaster began preaching this revelation and was instantly rejected and persecuted. A sect of the clergy known as the karpans was especially hostile as were another group, less clearly defined, the kawis. These were members of the noble priestly class who saw this new teaching as a threat to their status and sought to silence it swiftly. Zoroaster was forced to flee his home but would not renounce his faith.

He traveled to the court of the king Vishtaspa where he debated ultimate truth and the nature of divinity with the priests of Vishtaspa's court. Although, according to the accounts, he proved his claims, Vishtaspa was not pleased and had him imprisoned. While in jail, Zoroaster healed Vishtaspa's favorite horse, who had become paralyzed, and the king not only released him but became his first notable convert. The conversion of Vishtaspa marks the rise of the acceptance of the monotheistic Zoroastrian faith over the early polytheistic belief.

This new faith was founded on five principles:

- The supreme god is Ahura Mazda

- Ahura Mazda is all-good

- His eternal opponent, Angra Mainyu, is all-evil

- Goodness is apparent through good thoughts, good words, and good deeds

- Each individual has free will to choose between good and evil

The earlier gods, such as Mithra and Anahita, were demoted to spiritual emanations from Ahura Mazda and other entities were reassigned as well. The concept of the Chinvat Bridge was taken from the earlier faith where the newly dead had to cross a dark river by boat, and the process was known as the Crossing of the Separator. In Zoroastrianism, this became a bridge which narrowed for those who were condemned and became sharp as the edge of a razor, while for the justified souls it would open and become wide and easy to cross. Zoroaster also kept the vision of the two dogs who guard the bridge and welcome the justified while snarling at the condemned as well as the angel Suroosh, guide and guardian of the souls who protects them as they cross, and Daena, the Holy Maiden, who comforts the souls of the dead when they arrive at the crossing.

The world, according to Zoroaster, was alive with benevolent and malevolent spirits – the ahuras and the daevas – and one must guard against the influences of the negative while responding to the positive. Finally, it was one's own responsibility to live a life of truth instead of one based on lies and, if one honored one's creator, one would live a full, productive life and enjoy paradise after death.

Even if one failed at this, however, one's punishment in the House of Lies was not eternal. A messiah would come – the Saoshyant (“One Who Brings Benefit”) who would usher in the Frashokereti (End of Time) which would bring reunion of all souls with Ahura Mazda and everyone would be forgiven. Angra Mainyu would be defeated and everyone would live in bliss in the company of their creator, and those they felt they had lost to death, forever.

Zoroaster continued preaching this new understanding until his death at the age of 77. According to early accounts, he died of old age after a life of devotion to his god while later works claim he was assassinated by a devotee of the old religion.

Achaemenid Empire & Zorvanism

In 550 BCE, Cyrus the Great (r. c. 550-530 BCE) founded the Achaemenid Empire after a series of conquests and gave thanks for his success to Ahura Mazda. Since Zoroastrianism was long established in the region at this time, early scholars automatically assumed that Cyrus was a Zoroastrian, but this is not necessarily so. Modern scholarship has revised this opinion because Ahura Mazda was clearly invoked prior to the rise of Zoroastrianism as the Supreme Deity among many others in the same way the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II (the Great, r. 1279-1213 BCE) called upon Amun as the king of the gods. The invocation of Ahura Mazda by Cyrus, therefore, does not mean he was a Zoroastrian, even though it could.

This same argument has been applied to later rulers of the Achaemenid Empire such as Darius I (the Great, r. 522-486 BCE) and Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE) although, with these and later monarchs, it seems more likely they were Zoroastrian. Praises to Ahura Mazda appear in artwork, decrees, and dedications, notably at Darius I's great city of Persepolis and in the famous Behistun Inscription but, in keeping with the Achaemenid Empire's policy of religious tolerance, the faith of the royal house was not imposed on the populace. Every faith was welcome in the Achaemenid Empire and people were allowed to believe and worship as they pleased.

The encouragement of independent religious thought and expression gave rise to the so-called 'heresy' of Zorvanism late in the Achaemenid Period. Zorvanism developed directly from Zoroastrianism but differed from it significantly. In Zorvanism, the supreme deity was Time (Zorvan) who had created the twin deities of Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu. Ahura Mazda was still the creator but was no longer an uncreated, all-powerful being. In this system, Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu were completely equal in power, locked in a cosmic struggle which, even so, Ahura Mazda would eventually win.

Zorvanism & the Sassanians

Zorvanism developed further under the Parthians - whose decentralized government encouraged freedom of religious expression – but was fully realized under the Sassanian Empire. The Sassanians made Zoroastrianism the state religion but did not restrict the activities of other faiths, and it seems, many of the upper class were actually Zorvanites but, since the two systems so closely resembled each other, it is difficult to say with certainty.

The upper-class association with Zorvanism stems primarily from their tendency toward a fatalistic vision of life – at odds with the established pre-eminence of freewill in Zoroastrianism – which recognized the supremacy of Time in all aspects of life and how powerless human beings were in the face of it. The concept of que cera, cera - “what must be, will be” – best expresses the Zorvanite view which would be developed later in Persian art and poetry.

Whatever influence Zorvanism may have had on the monarchy, or Sassanian culture generally, the Sassanian kings clearly supported Zoroastrianism and were the first to commit Zoroaster's teachings to writing. Previously, the contents of the scripture now known as the Avesta were memorized and transmitted orally. The first Sassanian king, Ardashir I (r. 224-240 CE) supported the policy of written scripture as did his son and successor Shapur I (r. 240-270 CE) though the work was not completed until the reign of Shapur II (309-379 CE) and not fully realized in a final form until the reign of Kosrau I (531-579 CE). By the end of Kosrau I's reign, the Avesta and other works pertaining to Zoroastrian belief, practice, and values were codified in written form for the most part.

Christianity & Islam

Although the Christian faith was tolerated, and even encouraged, under the Sassanians, Christians did not return the favor and viewed Zoroastrianism as an evil system worshipping a false god. Toward the end of the Sassanian Period, Christians put out the fires in the outdoor Zoroastrian Fire Temples – the altars on which the flame of the god was to always burn – and preached against the faith, urging people to instead accept the “true faith” of Christianity.

By this time (4th century CE), Zoroastrianism had already influenced the development of Christianity via Judaism through concepts such as a single supreme god, the significance of human free will and an individual responsibility for salvation, a judgment after death, a heaven and hell, a messiah and an end-time, and a supernatural adversary an adherent must resist. These influences would later be instrumental in the development of Islam via Christianity and Judaism but, in both cases, Zoroastrian inspiration and example were not acknowledged and the faith was instead denigrated and demonized.

After the Muslim Conquest of Persia in 651 CE, Muslims destroyed the fire temples or replaced them with mosques, burned the libraries, and Zoroastrians were persecuted or killed if they would not convert. Many Zoroastrians fled the region for safety in India, where there remains a large Zoroastrian community to this day, while others either died for their faith or converted. Presently, Zoroastrian communities continue to flourish in many different countries, preserving the values of one of the oldest, and certainly most original, religious faiths in the world.